News & Events

Making assessments a teaching tool

Why do schools give students standardized tests? To check knowledge? Group students? Fulfill a requirement? Because they always have?

The answer is not always clear, even to educators. What could have been an opportunity for engagement and growth can instead be an intimidating moment that offers few benefits for students.

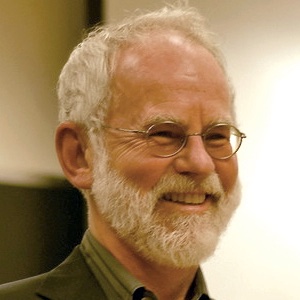

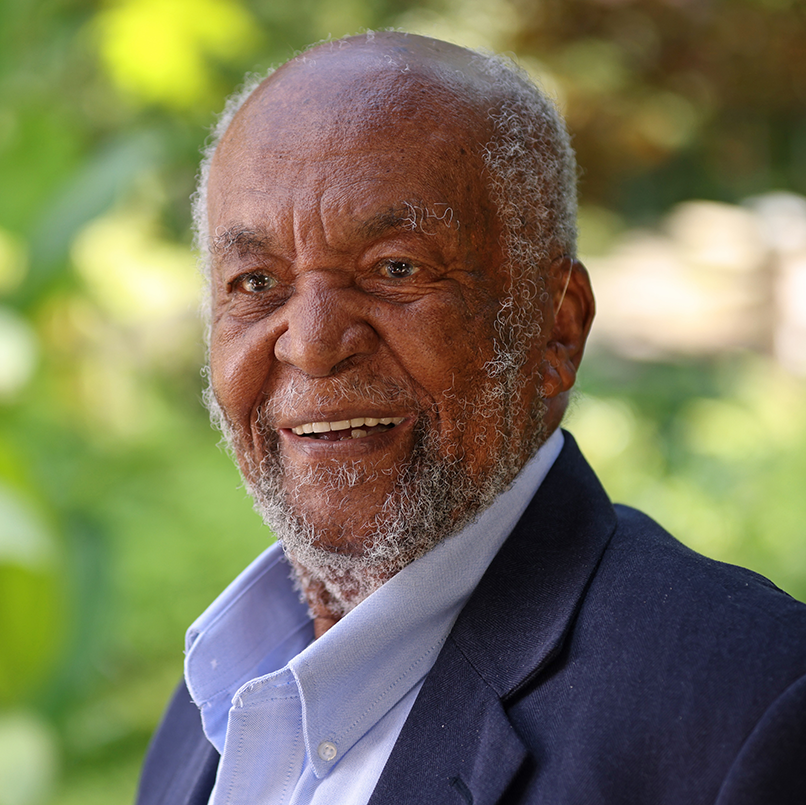

Assessments can and should serve a better purpose, according to McGraw Prize winner Dr. Edmund W. Gordon, who has dedicated his career to improving equity in every stage of education.

“Assessment should provide feedback that improves teaching and learning, rather than punish failure,” Gordon said. “Sorting mechanisms may serve institutional needs, but they rarely serve the learner. We should design assessments that affirm capacity, illuminate potential, and offer guidance.”

Gordon recently brought together a group of assessment experts for a special McGraw Prize webinar, “Re-purposing Educational Measurement to Better Serve Human Learning.” The panel, moderated by Eric Tucker, President of the Gordon Commission Study Group, included:

- Dr. Eva Baker, Distinguished Research Professor, UCLA

- Dr. Madhabi Chatterji, Professor Emerita of Measurement, Evaluation, and Education at Teachers College, Columbia University

- Dr. Neal Kingston, Distinguished Professor of Education Psychology at Kansas University

- Dr. Roy Pea, a 2022 McGraw Prize winner and Professor of Education and Learning Sciences at Stanford University

- Dr. Stephen Sireci, Distinguished University Professor at the University of Massachusetts Amherst

Here are key takeaways from the webinar:

Assess to teach, not to test

Baker, of UCLA, said there is an artificial separation between instruction and assessment that often leaves teachers guessing about what students have actually learned.

“Assessment should be seamlessly embedded in instruction so students can get better feedback and teachers can adjust in real-time,” she said. “We test at the end, when it’s too late to help. If we assess during the process, we’re actually enabling learning.”

Chatterji, of Teachers College, emphasized that formative assessment, when done well, gives both teachers and students critical information. Educators can adjust instruction and learners can monitor their own progress.

“We need to move from judgment to feedback. We must create systems where evidence of learning supports improvement—not just evaluation,” Chatterji said.

Personalization matters

Kingston, of the University of Kansas, is a leading figure in adaptive assessment design, which uses algorithms to adjust question difficulty in real time. These systems aim to offer a more precise measure of student ability and reduce test-taking anxiety. They offer a better path forward for assessments, he says.

“Technology allows us to create assessments that adjust to the learner. That’s a massive opportunity,” he said. “If the system changes as you engage with it, it can identify what you know—and how to support what you don’t.”

Pea, of Stanford, believes we need to move toward competency-based assessment: evaluating what students can do with their knowledge in meaningful contexts. That includes portfolios, interdisciplinary projects, and simulations that reflect the real world.

“Our assessments should validate complex performance—like how students apply knowledge to solve real problems,” Pea said. “If we want to cultivate lifelong learners, we have to stop measuring only short-term retention.”

Fairness is not a side issue–it's the central one.

Regardless of how they are delivered, Gordon and his peers all spoke about the need to make assessments more fair.

Chatterji warned that equity depends on how assessments are designed and used.

“When we ignore cultural context, when we use one-size-fits-all rubrics, we risk misrepresenting what learners actually know,” she said.

Kingston cautioned that using technology to create adaptive assessments built on biased content or flawed models would only extend current inequality.

Sireci, of the University of Massachusetts Amherst, said the problem requires rethinking what the test measures, how it’s interpreted, and how it’s used.

“Standardized tests too often reflect socio-economic advantage more than actual ability,” said Sireci of the University of Massachusetts Amherst. “We must develop measures that account for the full range of learner experience and identity … We can’t just tweak existing systems. We need new frameworks that begin with the learner in mind.”